I’m 71 now and have just published a book, “I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can‘. It begins on August 4, 1958 when I disembarked with my family at the port of Montreal, fresh immigrants to our new country. I was eight. I wanted to tell my story for my children and theirs, and have spent many months exploring my memories of the decades since. As I spelunked down some deep corridors I came across this story about the time I became a prison guard.

It’s 1971: I’m twenty-one and sitting in first year Criminal Law at UBC Law, the privileged, unenlightened son born into an upwardly mobile middle class family. Naive as I no doubt was, I was not unaware of my shortcomings. I didn’t know what I didn’t know but I did know one thing, I wanted to be a criminal lawyer. And I knew I was not ready for whatever being a criminal lawyer was.

Now that I was in law school, I knew I could learn in the formal academic sense what there was to learn, that was not my problem. I would have to do more than that; I would have to scuff my privileged leather soles on the sidewalk of life, get some ‘street’ if I was to ever succeed as a defence lawyer. And I did not have much time to get on with it. As it turned out, I would have to learn some fancy new dance moves as well.

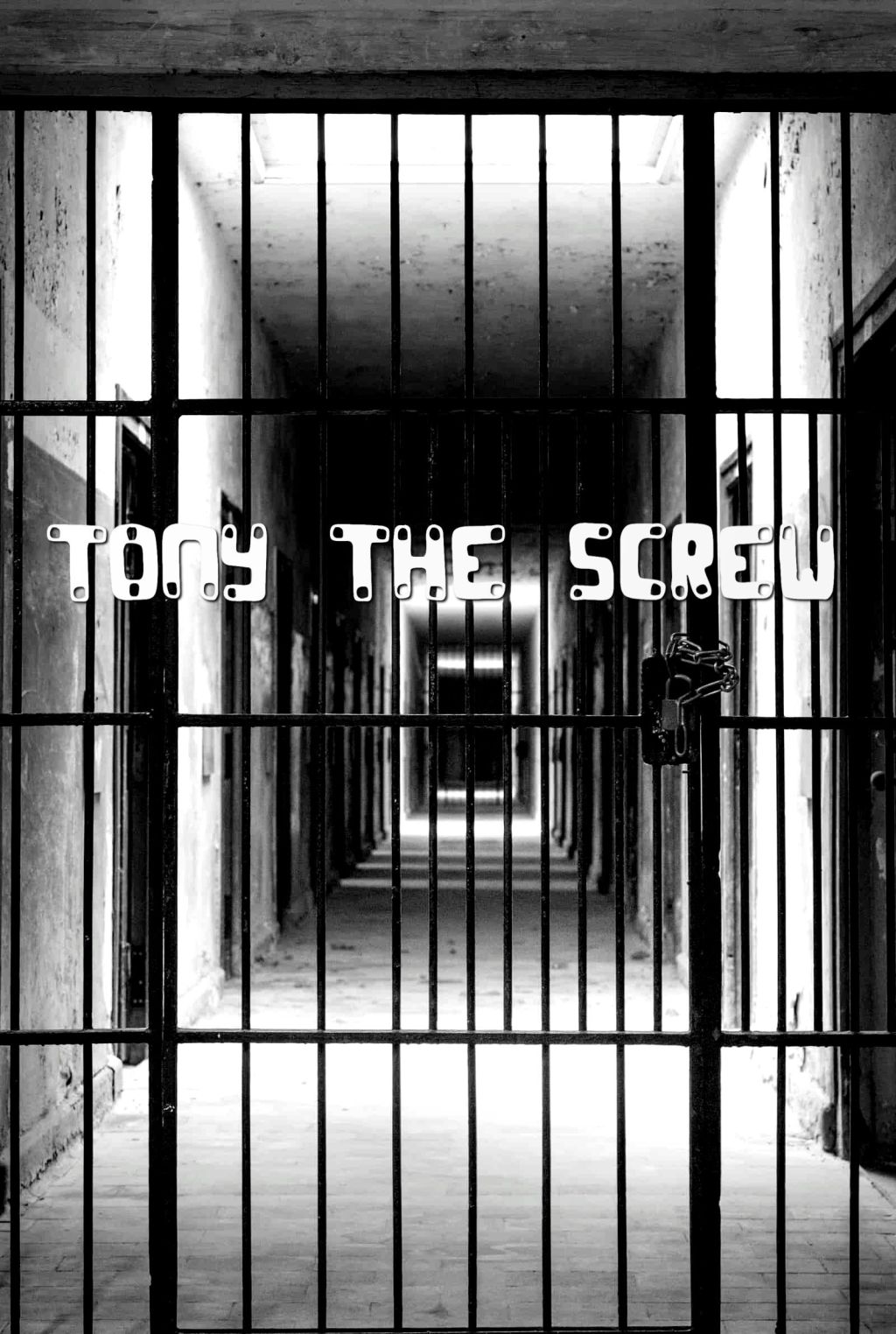

Walking down the long curved driveway toward the medium security prison in Burnaby was like walking onto the set of a horror film set in 19th century Victorian England. Oakalla was a prison built for two hundred and fifty men but was now ‘home’ to six hundred and fifty. I was a screw, a prison guard in Oakalla.

It was the summer of 1971 and I had just finished my first year law. I would never work in a place like Oakalla again, a place where nobody was happy, not the guards and certainly not the inmates. The sounds have stayed with me to this day; keys turning, metal gates, the concussive reports from steel, brick and concrete, inmates shouting and swearing, guards barking out orders, an endless metallic, profane symphony played by men behind bars.

I was not welcome. And I was not welcomed by any guards, this fresh young law school student who wanted to play at being a prison guard, thrown in amongst men who had been guards for twenty, thirty, forty years. “Who the fuck did he think he was!”

You’re locked in when you work in a prison, literally locked in, held ‘safe’ to the extent you are by a strange bargain struck between inmates and guards. ‘We outnumber you. We’re six hundred and fifty and you’re maybe thirty on any one shift. Don’t fuck with us!’. It was never said out loud, you could just feel the threat in the air.

Oakalla had a central hall into which all three wings of the prison flowed, designed as it was to control movement at all times. An inmate would be escorted by a guard to Centre Hall, “Prisoner from B Wing to A Wing”. The Centre Hall guard would alert the A Wing gatekeeper, accept custody of the prisoner and escort him to the A Wing gate. And there was a Golden Rule, breach it at your peril.

Always, always, always ensure that you are one on one in this human custody chain; one guard, one inmate. And never leave an inmate unattended when you are the Centre Hall guard. Never. These rules I was told on my first day and told with an air of menace, “Your personal safety depends on this.”

And so it went. My first couple of weeks orienting were uneventful. Shortly after, I was assigned to Centre Hall and I was to be the traffic cop. My real orientation was about to begin.

An old guard approached me at the B Wing gate, “Prisoner from B Wing to C Wing.” I already had a prisoner so I replied, “I need to clear this guy first.”

“Take him now!” he menaced, “I don’t have all day to wait for you.”

“But I have one already”

“God damn it kid, take him!”

I was uneasy but I did as I was told, my senses telling me something was wrong. I took the prisoner and ordered him to stand in place. He was short and strong and malevolent and there we were.

He knew the rules as well as I did and he understood the part he was to play and he was okay with that. He despised everything I was, my best days ahead, the best days of his life already lived. I knew instinctively I was in trouble.

“Stay there!” I ordered, pointing to a corner.

And he moved toward me. I looked around for help but there was none, no guards in sight. I was vulnerable and got set for what was now inevitable. The inmate attacked me. He was only 5’8” and physically I was a match, fit and strong in my own right, and willing but just wanting to retain control in a fight was no match for the dark hatred that fueled his attack.

The fight was on and here was my real problem, I had the Centre Hall keys and was in no position to open the gates. It seemed like a lifetime. I was in no mortal danger but I was in a fight I could not win. The ruckus raised, some guards raced down to the central office, retrieved a second set of keys and then came running to my aid.

I recall thinking two things as they pulled the inmate off me; that inmate was in for the beating of his life and I had been set up. To this day I think that to be the case. I was ‘being set straight’ by some guards who wanted no part of this ‘law student prison guard program’ and wanted to show that we were not safe. Perhaps I’m wrong, nothing ever happened again and nothing came of the incident. I expect there’s no record of it. I was not even asked for a statement. It was a dance lesson.

Oakalla was a wicked place, warehousing men in atrocious conditions, a place ruled by guards, a place with little oversight. I remember working in the Isolation Unit. It was underground with rows of cells barred by heavy metal doors. The interior of the cells were lit with one bare bulb, a bucket in the corner for defecating. It was inhumane, depraved and soul destroying. I watched as one young Muslim inmate was beaten by several guards and left with the ‘shit’ from his bucket smeared all over him. His ‘crime’? He had insisted on praying to Allah, not getting up when a guard came into his cell. It was the worst place I had ever been.

Sex is a commodity in prison. Small groups of inmates would parade together in their caramel coloured prison fatigues, their pants sewn skin tight on their bodies, cat calls following them everywhere as they circled the yard. I had never seen anything like it. It was survival, monetized and raw.

Many more memories flood back as I write but you get the point; the summer came and went, stripping a young Tony of some naivete and scuffing his dance shoes some. It was what I had wanted but nothing could have prepared me for that experience.

It made me more certain than ever that I wanted to be a defence lawyer, made aware that authority can be a place where darkness and bad men can hide, in plain view. Not all men of course, most are good men doing good things but some of them find a safe haven behind a uniform, protected by our essential respect for authority. And it is a safe place for evil to hide, protected from the light by uniforms and a ‘code’ that requires the adherence of each member.

Looking back it is where the righteous indignation that became so much a part of an older Tony, first took root. And it was also where I first dared to think, “Hey you got this. You can dance.” There were more lessons to come.

Leave a comment